Rediscovery of the sapphire from Bangka:

Parosphromenus deissneri

By Wentian Shi, 2018

In special thanks to P-Project and Peter Finke; Team Borneo and

my teammates Ji, Yuhan and Dai, Jianhui

Bangka Island is a very small island lies between Sumatra and Borneo, whose area is just about one thirtieth of Germany. It is a special biological bridge, where the species from Sumatra and species from Kalimantan meet each other, which leads to a great biodiversity. As a paradise of labyrinth fish and a witness of a great evolution in the past millions of years, Bangka is the home of 2 Parosphromenus and 5 Betta species. Parosphromenus deissneri is the swimming Sapphire of Bangka

It is a legend of a history of 150 years and the flag-ship species of her genus. Besides, the island is one of the two original locations of nominotypical subspecies of P. bintan, which is the most widely distributed species of this genus (from Sumatra, Bangka Belitung to Riau Archipelago). 3 of its 5 betta species are endemic ones: burdigala, chloropharanyx and schalleri; the first two are endangered species on the IUCN list;

Despite its great biodiversity, Bangka, as a separated small island, has never exported its fish commercially like Kalimantan or Sumatra due to the difficulties of transportation. Species like deissneri was only privately introduced into the West few times in the past 20 years by experts like Mr. Linke or Mr. Brown since it was re-descripted by Mr. Kottelat (Between its first description in 1859 and the re-description in 1998 the condition of this species remained unknown for almost 150 years.). The conditions of the habitats were also rarely reported since the first description, because of the inconvenience for travel.

In 2012 Mr. Zhou from China, Jungle Michael from Malaysia and Team Borneo from Japan conducted a search in Bangka. They checked all known habitats and found all 7 known species. Excited by their report I decided to find and keep deissneri myself in 2015. But the reality at that time was frustrating. I couldn’t find this species anywhere in EU. The Parosphromenus-Project informed me that all known strains of deissneri in the west were lost (later it turned out to be that at that moment this species was completely lost in captive around the whole world); and there was no visit to their habitats on the island since 2009, either (The 2012 expedition in the east was then unknown to the west.). With great concern and uncertainty about this legendary fish, I began my first visit to Bangka in 2016.

2016

I arrived in Pangkal Pinang in August 2016 together with my teammates Ji, Yuhan and Dai, Jianhui (Team N.J.B.). The severe damage to the environment of Bangka due to mining and oil palm planation was already visible from the plan. (Fig 1)

It was not a good sign for us. To find P. deissneri we planned to check all known Habitats (which kindly offered to me by Mr. Linke,), especially their Holotype locations. The actual situation of the Biotope was far more worse than we expected. The original habitats of deissneri were the small branches and swamps of the biggest river system of the island, which lies in the center area of Bangka. They were found by Mr. Kottelat and Mr. Linke in 1998 and 2008 in the middle range of this river, so called the traditional distribution area. But the whole area from the mountain, where the river origins, to the middle range was turned into a vast oil palm farm (at least 50 quadrat kilometer). The swamps and small branches there were severely polluted or destroyed by the oil-palm plantation (Fig 2)

The two known habitats were gone. The swamp with high population density in the past was completely dry. The small black water river was polluted by the farm and turned into a shallow muddy stream.(Fig 3)

We tried to walk through the remaining forest and find new locations with good water in the upstream areas, but what hided behind the trees was newly built oil palm farm. .(Fig 4)

The local people burned down the trees inside the forest, so that the farm would not be recognized from outside. We searched for 3 days, and we can’t find any proper water systems for parosphromenus in this traditional distribution area. What we got here was only the most robust Betta species, edithae. .(Fig 5)

which can survive in almost all water conditions. Then we turned south to the location of the new Holotype of deissneri, where this fish still existed until 2012. But the river was completely polluted in 2015 by a new oil-palm farm directly alone the river. The forest was burned down, and a pumping station for the palms was built directly beside the finding position of the Holotype in 1998. .(Fig 6)

Although the water conditions and water plants have already recovered in 2016 (black pH 4,8; GH<0,5). .(Fig 7)

Although the water conditions and water plants have already recovered in 2016 (black pH 4,8; GH<0,5). .(Fig 7)

and many fish species came back, the population of the P. deissneri was not reestablished. We searched around this location for 3 days and found only B. edithae, Belontias, Channas and Rasboras.

and many fish species came back, the population of the P. deissneri was not reestablished. We searched around this location for 3 days and found only B. edithae, Belontias, Channas and Rasboras.

Since all known locations were lost, we had to give up searching for deissneri. Instead we decided to collect the other important gem of Bangka, Betta burdigala. (Fig. 8)

This red endemic species, the swimming ruby of Bangka, is extremely rare, because it has only one habitat across the whole island, a small black water swamp at the far end of the island. Luckily, we found out that this swamp was still in perfect condition with perfect clear black water. (Fig. 9)

Unluckily, the swamp was so healthy, that the water level was too deep to catch small betta of coccina complex. Only 3 examples were collected in 2012, and we didn’t have the luck at our side this time. But we got chloropharanyx and were confident that burdigala was still swimming here.

At the last day we decided to check the habitats of B. schalleri and P. bintan. The region of these two species was relatively well preserved from human activities. We discovered a new river with clean water, where schalleri and bintan lived (Fig. 10, 11a, 11,b))

It was a deep (1m near the bank) fast flowing small river with half black water. The pH was around 5,1 with a cool water around 26-27 degree in the noon. It was heavily covered by plants along the bank. (Fig. 12)

and under the water the great colony of Cryptocoryne longicauda and bankaensis provided shelter for many fish sp.

(Fig 13 a, b, c)

In such a small habitat we managed to find 15 fish species, including Barbineas, goby, loach, juvenile of cat fish etc. It reminded me the real meaning of biodiversity in the tropic.

And in this spot, we met an unexpected rare guest: Sundadanio gargula (Fig. 14)

The endemic Sundadanio of Bangka. It was the first time that living samples of this species were photographed. My first trip to Bangka ended with great concern about the environment of this small island, and especially about the survival chance of deissneri.

2017

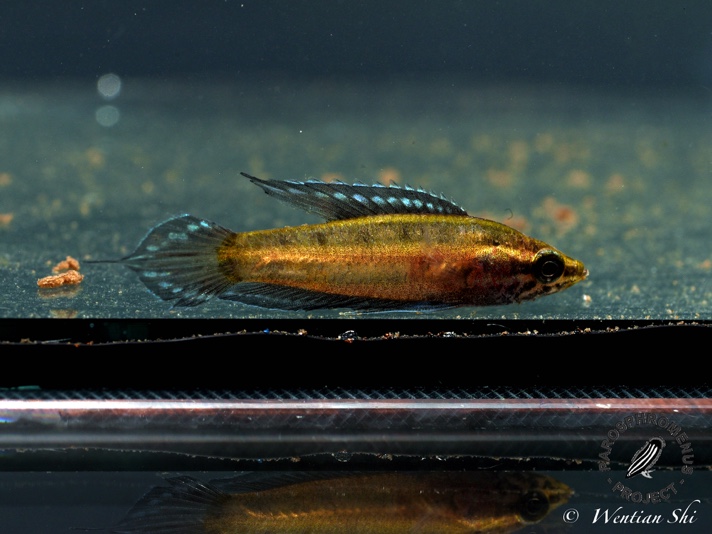

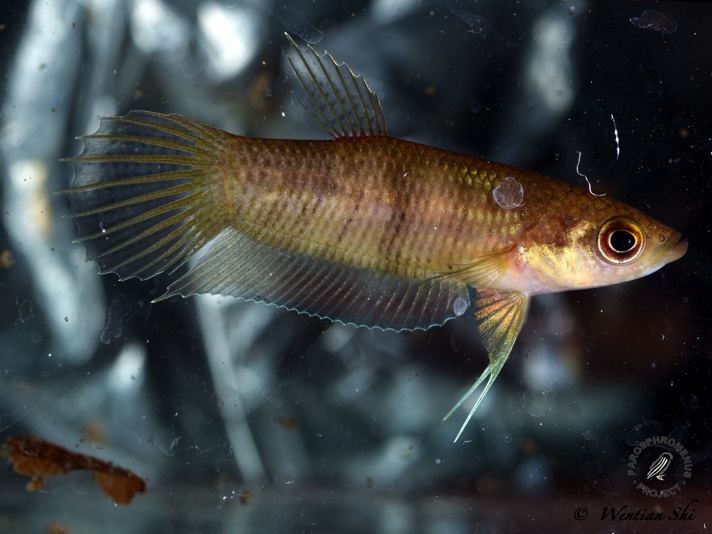

Although all known habitats of deissneri were lost, I didn’t want to give up. Thus, I checked for months on maps to find potential habitats of this species and got in touch with Team Borneo through the help of Mr. Finke. Six months later I arrived in Bangka for the second time in Mar. 2017 with my teammate Ji. We went directly to the location of the new holotype of deissneri. This time we drove around the oil-palm farm to the very upstream area. Then we went on foot along the river across forest to a small branch of the river, which is not yet polluted by the farm. I got it in my first try, a beautiful adult male with long filament on tail (Fig-15 a,b)

What a discovery! Finally, I rediscovered this fish. The water is clear not black, with a pH of 5.1, electrolytic around 6 μS/m at a water temperature of 27.8°C. The bank area of the river is around 0.5-1,2m deep and heavily covered by plants. The fish was hiding among the plants or in the holes under the wood, (Fig-16a,b,c).

We also found many Rasboras, chocolate gourami (Fig 17).

betta edithae, betta simorum etc. together with deissneri. But the population density of deissneri in this habitat was extremely low. We could get only less than 10 specimens from this area. The reason was that the water conditioned changed. According to all earlier reports deissneri lived in black water. The water in this river system was also once black in 2008. But in 2017 it changed into clear water in the upstream area, because of the deforestation. The Parosphromenus can adapt to clear water but cannot survive in a very high population as in black water system. Afterwards we decided to search the original habitat of the old holotype, where it was firstly discovered 150 years ago. It lies in the downstream area of the same river of the tradition distribution area. But the development of the small town and mine nearby has destroyed the forest and the river. No Parosphromenus could be found from their very first home anymore. In the following days we searched once again along the river of the traditional distribution area between the downstream position in 1859 and the middle area in 1998. But all my candidate locations failed me. We managed to find a beautiful very original swamp. The forest there was perfectly preserved. We even saw a group of monkeys jumping here and there (Fig. 18 a, b)

But the water was strange, half clean half turbid. I supposed in somewhere of upstream area the local people were burning down forest and digging canals for oil palm, which polluted parts of the water resource of this swamp (Fig- 19)

Therefore, we could not find any typical black water fish here.

After that we went to the swamp of burdigala. Unfortunately, the wonderful swamp was partly destroyed just in 6 months by illegal wood cutting (Fig. 20)

What remained can’t keep as much water as before. The huge colony of cryptocoryne bankaenesis downstream was also partly destroyed due to the bad water condition (Fig-21).

The water depth dropped to an average of just 30 cm. It was an ideal water level to catch burdigala (Fig-22).

But it did not promise a bright future for this species, because this swamp is their only habitat.

4 days after my arrival Team Borneo joined us. We went to his secret location, which was our only hope in the traditional distribution area of deissneri, where he caught hundreds of specimens in 2012. But the environment there changed dramatically. The earlier forests were replaced by oil-palm farm. The original black water river was now a half dry muddy stream, whose water was leaded by irrigation canals for the oil-palm (Fig-23).

Nothing remained. He lead us then to his location of the mysterious eastern type of deissneri. The rivers of this type were already polluted by Tin mining ten years ago (Fig-24).

Now the remaining forest in this area was also burn down to build houses. We decided to search around my new location. We found a huge swamp a few kilometers away of my location near anoher big oil-palm farms. But no deissneri lived there (Fig-25).

We confirmed the boundary of the current distribution of deissneri, that they are limited in the very upstream area. We turned back to the small branches in the upstream area and found two more small habitats. The problem is that, the habitats are all fragmental and are already partly affected by the human activities in this area. The rainforest and swamps are too small. The original black water changed into clear water. The fish struggled to adapt to the new environment. Thus, the population density of these habitats is very low.

At the end we decided to go into the heart of Bangka, which was never scientifically searched before, to look for new habitats of burdigala or deissneri. In this virgin land we succeeded to discover 3 more locations of deissneri, where we also caught B. simorum and B. chloropharanyx. . (Fig-26,27).

One of the new locations is a black water swamp, which hides in an untouched rain forest (Fig-28).

It is the only remaining black water swamp habitat of deissneri we have discovered. The fish from such water condition show magnificent dark blue color after capture, like a sapphire (Fig. 29)

I returned to Bangka 6 months later once again with my Teammate Dai, because we worried about the condition of that habitats. The scenes we had seen at that time were very frustrating. The process of deforestation in Bangka is so rapid, that just in 6 months one of the newly discovered habitats of deissneri in the remote area was burned down (Fig-30).

The illegal wood cutting also continued in the habitat of burdigala, and the water level dropped to no more than 10 cm. The burdigala struggled in the shallow muddy water. The only hope was the forest deep inside, where the local people not yet touched. We also checked the habitat of bintan. It was also in danger; the people were building house beside the habitat and constructed a wood water gate across the river (Fig-31).

The population of bintan dropped significantly. No bintan could be found down the water gate. Only a few of them were caught in the upstream area. Therefore, we searched further into the remote areas along the river system for bintan. We managed to find a huge black water swamp in perfect condition with very high population density of bintan (Fig-32).

But how further can we go next time? The island is limited. We can’t expect for hidden virgin land forever. Without protection, the loss of all habitats is only a matter of time.

2018

I went to Bangka for the fourth time six months later, in April 2018. The illegal wood cutting in the habitat of burdigala seems to be stopped, and the water level recovered completely. A warning sign from the local police was set up. It suggested that the local government might have taken some actions at last. Therefore, I believe that this habitat might survive for at least another 5 years. The habitats of deissneri seem to be also more or less maintained without big changes. But the survival of these habitats are only of a result of luck and under direct threat. Some new constructions of oil palm plantation near the habitat of the new holotype were already under way (Fig-33).

Another habitat for a Betta species was also in this period destroyed (Fig-34).

In so far, the expanding of oil-palm farms and Tin-mining continued without any limitation on this small island, I am not sure how long these habitats may last under the threat of the human activities. Although I rediscovered deissneri with great pleasure, at the very moment I realize in great sorrow that they are in great danger.

Keeping and Breeding in Tanks

To keep and breed deissneri in tank is not a difficult task. There are no specific requirements for this species in comparison with other parosphromenus species. They are not aggressive and can be kept in a group of 8-10 in a 50 L. tank (60X30 standard size) (Fig-35).

The male can reach a size of 4 cm, with a very long filament of tail. The filament itself can reach 0,5-1 cm long. The female is slightly smaller with no blue color on fins, but a dark red on the center of the tail. The female also has a short tip on tail, just arount 1mm long. The deissneri are very robust. They can adapt to different water conditions, even to a hard water of GH 15-20. They are not very sensitive to inorganic chemical parameters of the water, when in captive. But natural soft acid black water is much better for the fish, and they only dress up their metal blue color in such condition. I usually keep the fish in a black water of pH 5-5.5, GH 2-3. On the other hand, the organic factors are very crucial for them, which means they require a good nitrogen cycle. Deissneri are not picky mouths. They accept all kinds of living food animals: BBS, grindal, Moina, Culex-larva etc. The most difficult part of keeping wild catch deissneri is to work against Oodinium/pepper spots. They are very easy to be affected by these parasites. A regular water change is necessary, and an early treatment is very important when they get affected. With correct medicine they can be cured in a short time in early period of the affection. The tank breed generations are much stronger against Oodinium. They are rarely affected. They can live at least 2-3 years. I am not sure about the life span of this species in captive, since the wild catches are still active after 2 years. They should not be kept in warm water above 28 degrees. They can survive even when the water temperature is above 32 degrees. But it is not natural and will shorten their life spans. They live in cool water in wild. Even in dry season at noon the water is around 27-28 degrees. In the night it falls around 20 degrees or lower. According to my experience, for an apartment in EU with normal heating system an extra heating in tank is not necessary even in winter. It is only necessary if the water temperature drops below 16-18 degrees.

To breed them, a seperate tank for a single pair is recommended. The breeding tank doesn’t need to be very big, 10 L. to 20 L. is enough, but the bigger the tank the better for the female and easier to start a courtship. The courtship can last 2-3 days (Fig-36,37).

The spawning will last a few hours (Fig-38).

The female will leave the small cave, where the male guard the eggs in an underwater bubble nest (Fig 39 a, b)

The male may attack the female in this period. If the tank is too small, it may lead to an injury of the female. After 6-8 days the next generation will develop to a stage of being able to swim horizontally. They may stay in nest for an extra 2-3 days (Fig. 30)

Either a separate of the parents or the next generation is possible. The juveniles of deissneri are of a size of only 1-2 mm. They require small first food. Paramecium or small artemias are acceptable for the first week.

In the past 2 years I have visited Bangka four times. I have witnessed the dramatic environmental degradation happened on this Island. Oil palm plantation contributed the most severe damage to the rain forest. It happens not only in Bangka, but all over the whole Indonesia. For such a small island the loss of one swamp might mean the loss of one species forever. It took the nature millions of years to create the fabulous biodiversity in Bangka, it might just take a few decades to lose it forever. What can we aqua-fans do to prevent such a tragedy? I think currently the best answer is to preserve the habitat from human interference by purchasing it from the local people. It is also the standard protocol for the protection projects for Orangutan and Tiger in Indonesia. The big mammals get a lot of attentions from the public, but not the small fish like Parosphromenus or Betta under water. Thus, a private conservation area specifically established for small fish species might be crucial for their survival. For example, a tiny private land is purchased by my Japanese friend. He protects one Betta species permanently by doing so. It is proved to be an effective solution. This is also the aim and works of the Parosphromenus – Project, to evoke public attention and establish conservation areas for these species.